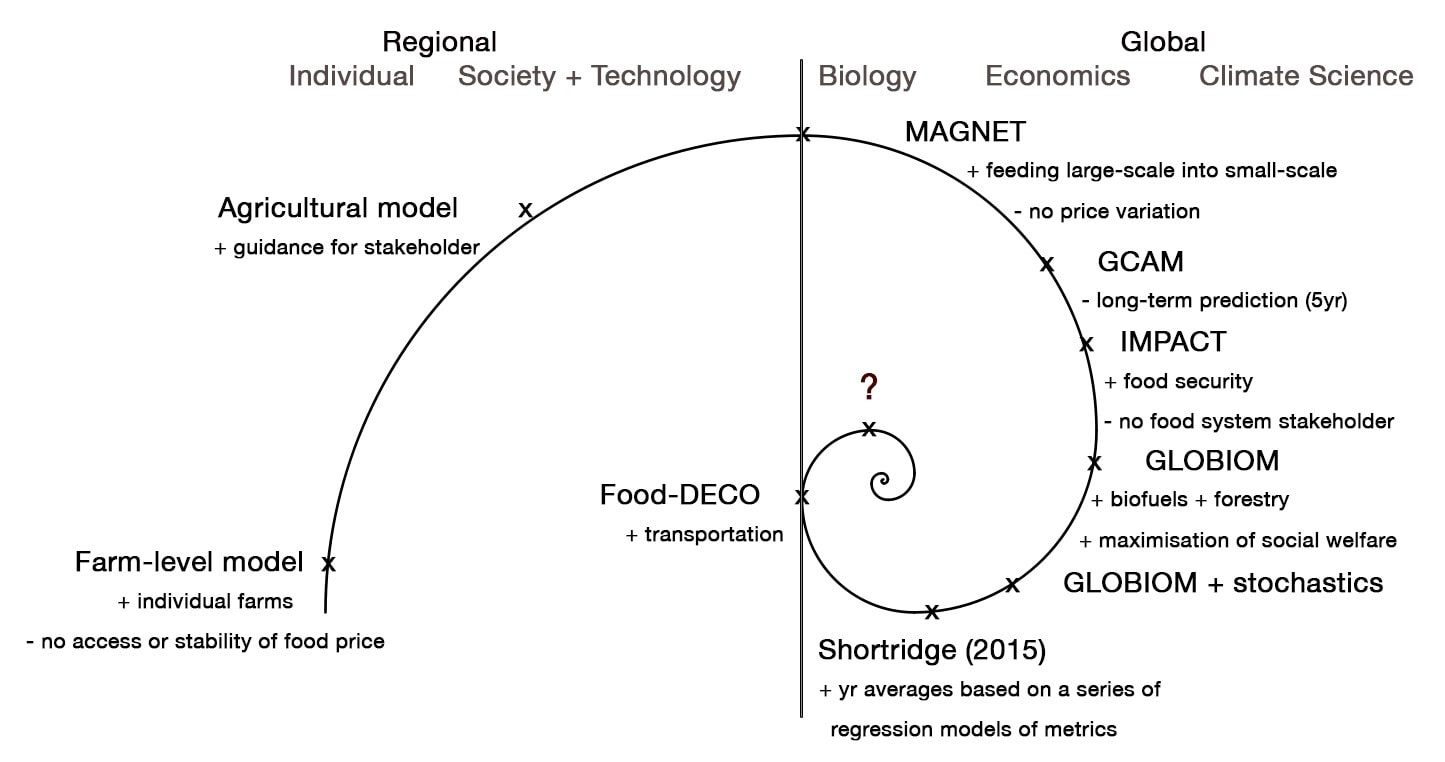

Credit: Anglia Ruskin University Credit: Anglia Ruskin University What conditions create that ‘perfect storm’ where food prices escalate wildly, leading to riots and unrest? Risk analyst Aled Jones (Anglia Ruskin University) is applying techniques he originally used to study the origins of the universe to answer that question – and help protect our food systems from the effects of climate change. “Making our food systems resilient to climate change is not just about producing enough food, as past events have shown. There have been cases where a small food production shock has had a high effect on food availability, and others where a massive physical disruption had no impact on food accessibility. It all depends on market forces and how governments handle the situation” says Aled. As director of the Global Sustainability Institute, he is applying mathematical data processing techniques to understand how social systems interact with agricultural production to ultimately determine food accessibility. One may presume that the most important factor is our ability to produce food in the first place, but Aled argues that price is the dominant issue. “Price has a greater effect on food access than physical access, since it determines who can actually afford food. But we are really bad at knowing what influences price when there are so many factors, such as markets, speculation and currency values”. With price being so critical, it is essential to know how this responds to disruptions in food production caused by increasingly frequent extreme weather events (so-called ‘food shocks’). To investigate this, Aled collaborates with the marketing and financial sectors, and, through the foreign office, multinational retail consortia and agrochemical companies. “Insurance companies are often ahead of academia in the sense that they have a lot of data about the conditions that surround food production shocks” he says. The traditional methods used to explore how these different sectors respond to food shocks include interviewing and ‘war game’ scenarios: “Essentially this involves locking representatives from markets and government in a room for a day and seeing how they respond to a hypothetical extreme yet plausible event that affects about 10% of global food production” says Aled. However, these methods are highly subjective and don’t always correspond with real-world situations. Searching for a more rigorous approach, Aled remembered his days as a PhD cosmology student, where he used image processing techniques to study telescope data on the cosmic microwave background: the oldest electromagnetic radiation in the universe. “I realised that those techniques of categorising information could provide new insights into food price data – uncovering new patterns and causal components”. Through the STFC Food Network+, he formed partnerships with the Department of Applied Maths and Theoretical Physics at the University of Cambridge and the UK Met Office. The aim was to review a range of analytical techniques for their ability to automatically detect food price shocks within datasets. “It’s really the same thing I did in my PhD: applying maths to clean up data and search for hidden patterns within the signals.” Besides tools from the finance and insurance sectors, these techniques include those used to detect earthquakes and exploding supernova stars. As Aled explains: “Normally people look at when a production shock or food riot has happened and then try to work out what it caused or what caused it. But this can miss cases where similar conditions led to different outcomes. Our aim is to find a technique that can objectively identify when a price shock has happened, what the characteristics of a price shock are and a way of categorising them.”. Having identified a number of promising algorithms, the group are now applying these to past historic events. Ultimately, understanding the conditions and market behaviours that combine to cause food scarcity will allow governments to be proactive and set in place protective strategies. “We hope these techniques can be used to develop hypothetical future scenarios so that governments, businesses and the insurance sector can ‘stress-test’ their plans to manage food shocks” Aled says. He also hopes that it could help develop policies that link up sustainability plans at regional, national and international levels. “Local food systems minimise environmental damage and carbon footprints, but if one is lost due to drought or a flood, you need links to the global system to survive. And when conditions are good, local systems can give their surplus to provide resilience elsewhere” he explains. Aled credits the STFC Food Network+ with giving him the time and space to try a truly novel idea. “This project has allowed us to take a more objective approach than traditional methods. By looking at historic price events and categorising them, we can then work with partners who explore the impact of weather on food production or the impact of prices on people, to better inform automatic models based on those behaviours.” Meanwhile, whilst this work occupies most of his time, Aled’s original love of astronomy has been rekindled through his young sons’ interests. “I now know more names of moons and dwarf planets than I did when I was actually studying astronomy!” he jokes. It just goes to show how creative thinking and interdisciplinary partnerships can generate truly novel solutions to improve our food systems.

0 Comments

|

AuthorJune 2024 - Archives

June 2024

Categories |

- Home

- Webinars and Events

- About the SFN+

- News

- Blog

- Expert Working Groups

- Funding

-

Publications

- Bioeconomy positioning paper

- SFN+ 5th Annual Conference

- OMM Policy Report

- ‘Multi-Stakeholder International One Day Workshop on Organic Agri-Food Value Chains for Net Zero’ Report

- SFN 2050 UK Net Zero Food report

- Sustainable Cold Food Chain Booklet

- Food Sensing Technologies for Safe and Nutritious Food

- Sustainable urban and vertical farming

- Projects

- Join/Contact Us

RSS Feed

RSS Feed