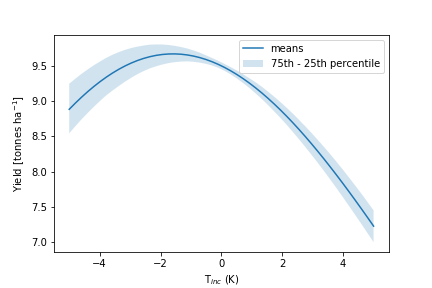

Mean yield as a function of mean temperature change relative to current baseline. The model predicts relative reductions in yield of ~4% with a mean temperature increase of one degree Mean yield as a function of mean temperature change relative to current baseline. The model predicts relative reductions in yield of ~4% with a mean temperature increase of one degree Climate change is widely claimed to be the biggest challenge facing humankind and is already impacting farmers in some of the world’s poorest regions. Adapting to rapidly-changing weather patterns will be critical if we are to produce enough to feed the growing population. Big Data could be a key instrument to achieve this as Seb Oliver has been demonstrating with his STFC FoodNetwork+ supported project: Forecasting Agricultural Crop Yields at National scales (FACYNation). An astrophysicist at the University of Sussex, Seb is certainly comfortable with using Big Data. His particular specialism is tracking the evolution of galaxies using infra-red light captured by satellites and telescopes. More recently he has become interested in Big Data approaches for more ‘down to earth’ problems, including projects in the medical sector to coordinate patient records over time to improve diagnosis. An introduction to Met Office climate scientist (and former astrophysicist) Edward Pope during the 2018 February STFC Food Network+ Sandpit event inspired an idea to build a modelling tool that could increase the climate-resilience of food supply chains. In the near future, entire regions are projected to experience new temperature regimes, so it is vital that we can forecast how different crops would respond. “One approach would be to use our knowledge of plant biology” says Seb. “But this requires detailed physiological understanding and these forecasts may not correspond with our observations in the field”. To brainstorm new approaches, Seb organised a two-day ‘hackathon’, which brought together meteorologists, theoretical physicists, data scientists and specialists in machine learning. Ultimately, they opted for an empirical approach that converted actual data, in this case USA maize yields and meteorological records, into a model describing the relationship between maize yields, temperature and precipitation. This used a Bayesian modelling technique, originally applied by Seb’s postdoc Peter Hurley to solve astronomy challenges. “A key advantage is that this model is based on actual observations, hence no detailed knowledge of physiology is required” Seb says. “It is also more useful than simple correlation methods since these are only really accurate for slight variations, rather than completely different scenarios.” Another advantage is that the Bayesian approach allows further variables to be added easily, such as soil conditions or pollution levels. Having demonstrated proof-of-concept with maize grown in the USA, Seb and the team are keen to develop the model for different crops, countries and varieties. “We are also investigating new sources of data, for instance earth-observation photographs to quantify yields from banana plantations” Seb says. Ultimately, he hopes the model will become a freely-available, open-source platform that researchers around the world can develop and contribute to. Since the model’s algorithms don’t require super-computers, farmers in developing countries could particularly benefit from it. Nevertheless, for the next stage he is focusing closer to home by developing a model for UK wheat breeders. Currently, new varieties of wheat are trialled by growing them at specific test sites and measuring the average yield over five years. However, the results at these sites may not reflect the variation that would be seen if the crop were planted over the whole UK. Through an extension grant from the Food Network+, Seb is now helping to develop SIMfarm 2030: a model that can use the initial test results to predict how new varieties would perform across the whole UK. This is being led by plant physiologist Jake Bishop (University of Reading), who specialises in how crops are affected by stressful weather conditions. Potentially, SIMfarm 2030 could hypothesize the best-suited varieties for different climate-change scenarios. “This project came from the success of FACYNation and builds on the Met Office’s “food and farming” research programme sponsored by the Government’s Department for Food, Environment and Rural Affairs” Seb says. Throughout this work, collaboration has been – and continues to be- a strong theme, engaging researchers across disciplines, from PhD students to Professors. Having convened interdisciplinary meetings in the past to investigate how to apply data science to global challenges, Seb appreciates the strategic role of networks such as the Food Network+. “Events like the STFC Food Network+ Sandpits are so important because bringing people together is key” Seb says. “As data scientists, we have valuable tools to offer but we don’t necessarily know where the problems are”. Seb also credits the Food Network+ for supporting a sector of the knowledge-transfer chain that can struggle to attract funding. “Taking knowledge and theory to the next level of practical application can be challenging” says Seb. “But having proof of principle gives us a stronger case to take to investors and stakeholders”. Outside work, Seb’s fascination with models continues. “I like to play board games, especially strategy games such as ‘Ticket to Ride’ and ‘Pandemic’ he says. But I am always trying to work out the mathematics of the game!” No doubt, it won’t be long before the real world presents another challenge for him to get his teeth into…

1 Comment

|

AuthorJune 2024 - Archives

June 2024

Categories |

- Home

- Webinars and Events

- About the SFN+

- News

- Blog

- Expert Working Groups

- Funding

-

Publications

- Bioeconomy positioning paper

- SFN+ 5th Annual Conference

- OMM Policy Report

- ‘Multi-Stakeholder International One Day Workshop on Organic Agri-Food Value Chains for Net Zero’ Report

- SFN 2050 UK Net Zero Food report

- Sustainable Cold Food Chain Booklet

- Food Sensing Technologies for Safe and Nutritious Food

- Sustainable urban and vertical farming

- Projects

- Join/Contact Us

RSS Feed

RSS Feed